Kelsey: A Name Rooted in Sound

We wanted to tell you something of the story behind the Kelsey name and the man who started it all, Bill Kelsey. So, we’ve had a trawl through the history books to help give him his due. It’s a rich tale, filled with names that stand tall in the annals of the live sound business . . .

If you’re hungry for more of the wider history of live sound (and how could you not be?), there are plenty of great articles available online, some of which we’ve drawn on here (and we’ve included links where possible for your further pleasure!). We hope you find this as enjoyable as we have . . .

Kelsey: A Name Rooted in Sound

Kelsey Acoustics has long been known as one of the top providers of interconnectivity solutions for pro sound. Today, the British company’s cable and connector infrastructure packages tour the world with leading artists and are installed in studios, theatres and venues everywhere.

Take a look at Kelsey’s long list of clients and you’ll see names such as Abbey Road and Metropolis studios, Glastonbury, V and Homelands festivals, plus touring artists such as Radiohead, Björk, Robbie Williams, The Killers, Jamiroquai, Mel C, Dua Lipa, Billie Eilish and many more. If you’ve been to a few gigs or theatre shows in the last 30 years, the chances are you’ve listened to sound that’s been delivered down a Kelsey cable.

But fewer people know the Kelsey name has figured in pro sound for far longer than that. Bill Kelsey’s story in audio stretches back to the pioneering days of live sound systems – to the days before the pro audio industry could really lay claim to the words “pro” or “industry” . . .

Bill Kelsey himself was one of the brilliant pioneers of that time, when everything that we know of pro sound today still remained to be done. Beginning in the late 60s and through the early 70s, he became an influential figure in the early development of audio electronics and PA systems. His presence in the business at that time would impact the electronics design ethos that would shape the world of live sound processing for years to come, and he played a central part in helping the great live acts of the era to be heard . . .

Straight Outta Compton

In the late 1960s, Bill Kelsey was an engineer at the Compton Organ Company in London. This famed manufacturer of pipe organs for cinemas, churches and dance halls had been going since the glory days of the 1920s, and many an organist had risen through a theatre floor seated at a Compton. But now, the company was making its ‘Electrone’ organs, which used a tone-wheel technique, like that of the Hammond organ. Kelsey likely suspected at this time that, with the emergence of solid-state electronic circuitry, Compton’s technology was fast becoming obsolete.

It was around this time, in 1969, that Kelsey met a new, young recruit who arrived at Compton’s with a degree in electrical engineering. This enthusiastic young man was Graham Blyth, a skilled organist, who would go on to become one of the audio technology world’s major driving forces.

The two men formed a successful bond and Kelsey became a significant figure in Blyth’s early career. “All my early designs were heavily influenced by my mentor, the late, great Bill Kelsey,” said Blyth in an interview with Systems Contractor News in 2007, “and I spent a lot of time just fiddling, making useful improvements to his work.”

While training him in the design and lay-out of printed circuit boards, Kelsey also imparted the ethos that would stay with Blyth throughout his stellar career. Speaking in a 2011 interview for NAMM’s Oral History program, Blyth recalled, “Bill was a wonderful guy, and he taught me a lot. He probably didn’t think he was teaching, but he was. And he said, ‘Elegance, Graham, that’s the most important thing. Always be elegant!’ – in your design, in terms of how you lay out your circuit board, how your circuitry should be elegant and sensible and practical. ‘Don’t make it too complicated’ is really what he was saying.”

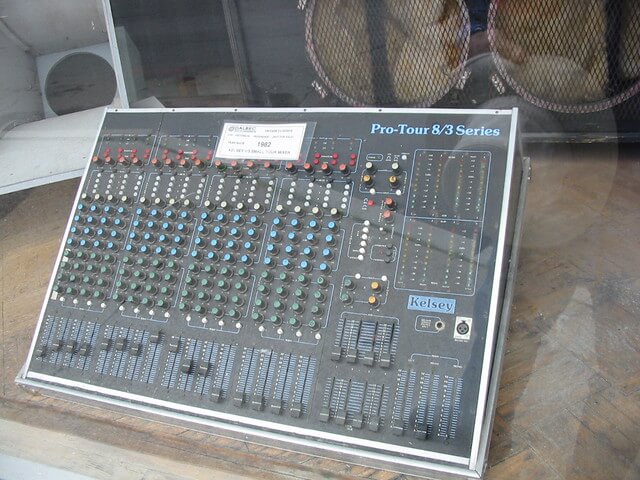

Blyth soon left the failing Compton, and took a job working on sonar systems, but in his spare time he continued to work with Bill Kelsey on audio electronics. Perhaps sensing the end for Compton, Kelsey had a major personal project underway: designing and building a 40-channel mixing console for a new London-based prog rock band – Emerson, Lake & Palmer (ELP). Blyth remembers, “I used to go up every night to Alba Place in Notting Hill and help him build it – you know, stuff things into circuit boards, solder them up, do a bit of wiring.”

The console Kelsey and Blyth built was used for ELP (and others) at the legendary Isle of Wight Festival in August 1970. Following his mixing desk success, Kelsey joined forces with Jim Morris, and started Kelsey-Morris, “and I . . . went and worked with him,” Blyth recalled. But it was a relatively short-lived appointment, as history was calling. Blyth left Kelsey-Morris and joined ex-Led Zeppelin sound engineer Phil Dudderidge, at his company Rotary Speaker Developments (RSD). This was another maker of mixers, also derived from a Kelsey design, for clients including Roy Wood’s Wizzard, and Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel. Blyth and Dudderidge would, of course, go on to create mixer manufacturing giant, Soundcraft.

Days of WEM and Roses

As a specialist audio company, Kelsey-Morris continued working on Kelsey’s mixer designs, as well as spearheading the next big trend in live sound PA systems, as new formats for live use began to take off in Britain. Before this, the must-have live sound reinforcement system had been Charlie Watkins’ iconic WEM columns, used by the biggest acts of the day including Jimi Hendrix, The Who, The Byrds, Led Zeppelin, David Bowie, Janis Joplin, Cream and Pink Floyd. Kelsey and others would change this landscape.

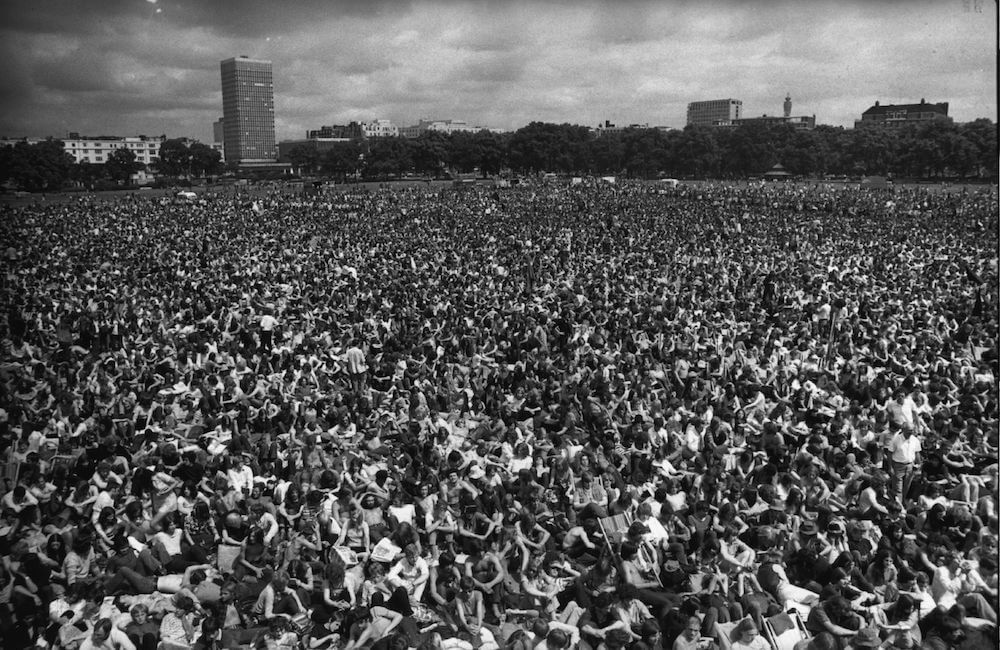

Watkins is a unique figure in the history of live sound. He was a quiet, short, balding, charming, accordion-playing engineer who didn’t like rock music, but counted Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie and Marc Bolan as friends. Watkins’s WEM columns provided sound (which could usually be heard by the audience – a big plus at the time) for most of the biggest performing artists of this remarkable period. And he was eternally popular with all of them. He’d proved the doubters wrong by creating a 1000W sound system for Harold Pendleton’s Windsor Jazz & Blues Festival of 1967 (thanks to his pioneering concept of amp ‘slaving’) and WEM systems were on duty at the Isle of Wight Festivals of 1969 and 1970. He was also behind the first ever quadrophonic performance, for Pink Floyd.

But things were changing. The new-style PA designs taking over from the WEM era became known as ‘bin and horn’ systems and were more efficient than columns at throwing out sound. Kelsey-Morris created what was one of the very first available for sale in Britain, with customers including King Crimson, T. Rex, Ten Years After and later, Pink Floyd. The systems were based on technology borrowed from cinema sound: bass and mids from an RCA W-Bin, with a Vitavox radial horn mounted on top for the highs. The whole assembly stood almost 2.5m tall – and understandably, moving it was an ordeal for the poor crew.

Watkins knew when he’d had enough of a good thing, and left the live sound market for good in 1974. Talking to Gary Cooper for Sound on Sound magazine many years later, he recalled the various reasons for his decision. One was his passion for the accordion (he would go on to develop the reference standard amplifier for the world’s top accordion players!), while another was his growing concern with reports that exposure to noise caused hearing damage: it worried him that he could actually be hurting people.

But Watkins also mentioned another, coinciding factor: “Kelsey and Morris had come out with a version of the W–bin at about that time, but their system was better than the W–bin and they were better than me,” he said. “Although they were terribly heavy to carry, I could see what was going to happen. There they were with a 500-watt box against a great big WEM system, and it seemed like it was time for me to hang up my headphones. So, I just stopped.”

Floydian Slips

In ‘Welcome to the Machine: The Story of Pink Floyd’s Live Sound’, published in Sound on Stage magazine in 1997, author Mark Cunningham gives a fascinating snapshot of how Kelsey’s path crossed with Pink Floyd.

In May 1971, the band’s sound engineer and road manager, Peter Watts, booked the Granada Theatre in London’s Wandsworth Road to test out a new 2-way passive PA design, from Bill Kelsey. As Cunningham relates, the day stuck in Kelsey’s mind . . .

[Bill Kelsey recalls] “What happened was indicative of the way the Floyd used to do business in the days when they were more of a cult band. Peter Watts and Steve O’Rourke (Floyd’s manager) said they’d like to try a system, so I went down with all the gear, and then found there was another PA company there and that it was to be an A/B test. Feeling a bit miffed that I hadn’t been told, I set up the gear as did the other company, and they tried it out with the mixing console at the back of the hall.

“It seemed to be going all right, but Peter said, ‘To be quite frank, I’m disappointed – it’s rubbish’. And Steve cut in, ‘You realize you’ve wasted my whole day, not to mention the cost of the hall?’ Peter continued to push up one fader to produce this horrid, muffled sound, while the second fader produced a nice, clear sound. I just wanted the ground to open up. Suddenly they both burst into laughter and admitted they’d crossed the whole thing over.”

“Despite the elaborate wind-up,” says Cunningham, “Kelsey’s system was taken on board at the beginning of the following year.”

As well as leading the ‘bin and horn’ charge, Kelsey-Morris made an important contribution with crossovers. By the early 70s, with loudspeaker drivers becoming increasingly powerful, system designers found that existing crossover technology was no longer up to the job. Sitting between the power amplifier and the loudspeakers, the crossovers would struggle to cope, often with smokey and bad-sounding results. Kelsey’s solution? Put the crossover before the amplifier. As Ben Duncan describes in his brilliant History of PA, “This took the crossover out of the dicey high-power region, so it shrunk dramatically in size. The (passive) circuit was simple, needed no power, and for bands like Pink Floyd, it was built — at their insistence — in an Old Holborn tin.”

Kelsey-Morris’ PA system designs moved on to typically include newer Electro-Voice or JBL drivers, but despite the increasing sophistication the issue of the cabinets’ size and weight remained. It was a problem that Kelsey was keen to address, so he tasked a young Australian engineer he knew, who had an interest in loudspeakers, with designing a less cumbersome bass solution. That engineer’s name was Dave Martin – future founder of the mighty Martin Audio.

One roadie remembered Kelsey and Martin well. Joining Pink Floyd’s road crew at this time was the late Marek “Mick” Kluczynski, who would go on to become a revered production manager in the live touring industry, technical director of the BRIT Awards and winner of a TPi Lifetime Contribution Award in 2005. Once again, we turn to Mark Cunningham for the story of Kluczynski’s first gig with Pink Floyd.

“Kluczynski recalls that his first show as a crew member, the opening night of this tour [January 20th, 1972] at the Brighton Dome, ended in disaster. He says, ‘In those days, we didn’t understand how to separate power sufficiently between sound and lights. That was the only show that we had to cancel and reorganize, because we were all sharing the same power source. The Leslies on stage sounded like a cage full of monkeys, because they were sharing a common earth. It was the very first show that any band had done with a lighting rig that was powerful enough to make a difference. So we had this wonderful situation where the fans were actually inside the auditorium, and we had Bill Kelsey and Dave Martin at either side of the stage screaming at each other in front of the crowd, having an argument’.”

It wasn’t long before Martin took the opportunity to do his own thing and went off to start Martin Audio. Soon after his departure, Kelsey engaged another young engineering prodigy who had been producing his own PA systems for a while, in a kind of friendly rivalry with Kelsey-Morris. His name was Tony Andrews, and his role, like Martin’s had been, was to design more compact solutions. And like Martin, he too would go on to achieve legendary status in sound reinforcement – first with Turbosound and later with Funktion-One. Among Kelsey’s great skills was, it seems, a good nose for talented engineers.

Signaling Change

Forward to 1978, and Kelsey, now without partner Jim Morris who had ‘gone elsewhere’ in 1974, took the decision to sell the company to an employee, a former roadie called Richard Vickers (or ‘Dick Vick’ to his friends, of which he had many). Kelsey and Vickers had likely encountered each other through their links with ELP – Kelsey as the creator of their 40-channel mixing console in 1970, and Vickers as a member of their touring crew – although Vickers had also worked on the road with another Kelsey customer, King Crimson.

Vickers’ ownership signaled a change of direction for the company, which was renamed as Kelsey Acoustics that year. He saw the big opportunity of the future in infrastructure solutions, in enabling standard, purpose designed cabling and connectivity packages that were built for the road, that saved setup time and could be cross-rented by the hire companies of the day. For the next 20 years, Vickers made this the next phase of the Kelsey success story – as a go-to supplier for essential audio infrastructure.

Sadly, Vickers passed away unexpectedly, after a short illness, in 1998. It was a terrible loss for all concerned, but the work Vickers had put in to making Kelsey Acoustics a mainstay supplier stood the company in good stead. Ownership was taken on, as Vickers had wished, by his friend Tony Oates, owner of one of the UK’s biggest names in pro audio distribution of the 1990s, Fuzion. Tony recalls his first meeting with Richard.

“When I began with EV in mid 1982 one of the early calls was from Mr Vickers. He was being extremely rude and venting his unhappiness that EV had not handed the line to him (because he believed he was doing most of their UK biz). I stopped him mid-flow, asked who he was and where he was – then I got in my car and drove to Notting Hill. After a shaky start we ended up in the pub, a phone call was made and it turned into a long evening – by the end of which we were not yet best mates, but the potential had been identified.

With Tony’s and Fuzion’s influence Kelsey became one of the leading name’s in Pro Audio infrastructure, supplying many prestigious Artists with solutions still In use today.

Today the company is thriving under the guidance of one of Vickers’ recruits, Tony Torlini, and busy planning for the next generation of pro audio. What does the future hold? Well, their story has seen success in audio processing and sound systems, and more recently infrastructure and interconnectivity have been at the company’s heart. For Kelsey Acoustics, the future might just be a combination of both. Watch this space . . .